This journey from the centaur’s internal conflict to Ganesha’s harmonious union teaches us that a truly global and compassionate way of “becoming with animals” blossoms not from imposing one culture’s anxieties, but from cultivating the wisdom to recognize and support the diverse, hybrid partnerships where humans and other beings can genuinely flourish together.

Imagine standing in the lush, green forests of Southeast Asia. An elephant, magnificent and intelligent, approaches with its caretaker, a mahout whose family has worked with these animals for generations. As a visitor, you’re faced with an ethical crossroads. The tourist camp offers direct contact with elephants and the chance to ride them, an act that feels increasingly suspect. The alternative is to watch from afar, an act that feels safe and allow the elephants freedom, but detached, denying you the opportunity for meaningful interaction. This modern dilemma, felt by countless travelers, is not just about a single choice; it is the result of a deep, often unseen clash between two profoundly different cultural stories about our place in the natural world.

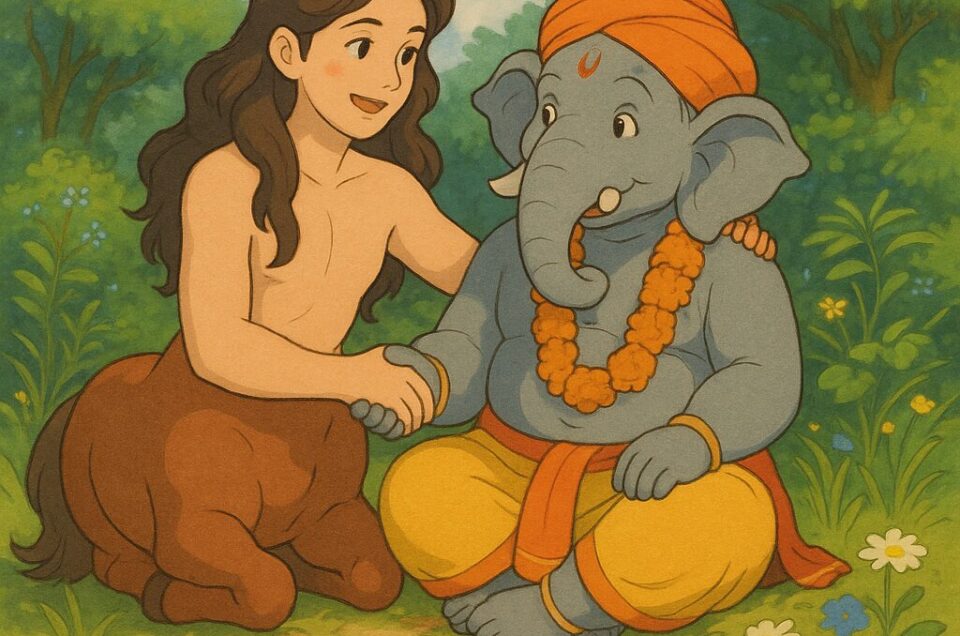

This conflict can be understood through two powerful mythological figures: the centaur of ancient Greece and the elephant-headed god, Ganesha, of Hindu tradition. They are more than just myths; they are windows into the soul of a culture, revealing how we see ourselves in relation to the animal kingdom.

The centaur, a seamless fusion of a man’s torso and a horse’s body, is a potent symbol of the West’s long and often troubled relationship with nature. With the exception of a few wise figures, centaurs in Greek mythology are typically depicted as wild, violent, and driven by untamed passion. They represent a deep-seated anxiety: the fear that our “higher” human reason will be overwhelmed by our “lower” animal instincts. The centaur’s story is one of internal conflict, a battle between civilization and wilderness that must be won through control, domination, or—if that fails—separation.

When this “centaur mindset” is applied to the complex issue of elephant tourism, it instinctively frames the relationship between the mahout and the elephant as a power struggle. It sees the use of tools for guidance as instruments of domination and the act of riding as an assertion of human supremacy. From this perspective, the only truly “ethical” solution is to end the conflict by enforcing a separation. This leads to the well-intentioned belief that we must not interact with the elephants at all, creating a relationship based on a distant, observational gaze rather than direct contact.

The East, however, offers a different foundational story. Ganesha, one of the most beloved deities in Hinduism, whose influence is felt across Asia, presents a vision not of conflict, but of divine synthesis. With the body of a person and the head of an elephant, he is a symbol of perfect integration. The elephant’s qualities—its immense strength, loyalty, and profound wisdom—are not wild passions to be suppressed, but divine attributes to be revered and fused with human form. Ganesha is the “Remover of Obstacles,” a benevolent guide who embodies the harmonious union of animal power and spiritual intelligence.

This “Ganeshan mindset” fosters a worldview where humans and animals can be partners in a shared existence. It provides a cultural framework for understanding the traditional mahout-elephant bond not as one of master and slave, but as an intricate, intergenerational partnership of communication and mutual reliance. The goal is not to separate from the animal, but to live well together, acknowledging a deep, shared history.

The problem arises when the Western, centaur-like story of conflict is projected onto a culture whose relationships are more Ganeshan in nature. This leads to a form of well-meaning but intrusive judgment, where Western tourists or organizations, unfamiliar with the deep local context, condemn practices they do not fully understand. They risk dismissing the profound skill and knowledge of mahouts and ignoring the complex social and economic realities that tie the welfare of elephants to the welfare of the communities that care for them.

So how do we bridge this cultural divide? The philosopher Donna Haraway offers a powerful concept: hybridity. She argues that we must abandon the fiction that nature and culture are separate. We are already, and have always been, deeply entangled with other species. The goal is not to “purify” these relationships by creating distance, but to acknowledge our shared, messy existence and take responsibility for making it better.

In her book When Species Meet, Haraway even discusses the centaur, not as a symbol of conflict, but as a metaphor for the skilled, hybrid being created by a horse and rider in a true partnership. This idea of hybridity asks us to move beyond a simple “hands-off” policy. Instead of just asking, “Is this activity exploitative?” we should ask, “What kind of relationship is being fostered here?”

For elephant conservation, this means supporting elephant tourism that focus on the elephant’s entire well-being—its social life, its psychological enrichment, its health—rather than just enforcing a “no-contact” rule. It means valuing the deep bond a mahout can have with their elephant and supporting models where this relationship is based on trust and communication. It requires us to trade simple, absolute rules for a more complex and engaged form of ethics.

Ultimately, the stories of the centaur and Ganesha teach us that there is more than one way to live respectfully with animals. True global conservation requires cultural humility. It asks us to recognize that our own myths are not universal truths and to appreciate that the most ethical path forward is not one of separation, but one of “staying with the trouble”—of learning how to foster better, more compassionate, and more responsible partnerships with the other magnificent beings who share our world.

![[1] Q: Are Elephants in Tourism Wild or Domesticated?](https://manifatravel.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/elephant-vet4-780x636.jpg)

![[2] Q: Is elephant riding harmful?](https://manifatravel.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IMG_5363-960x636.jpg)